North Walsham Guide

North Walsham's origins and place in history

North Walsham's origins and place in history

The Anglo-Saxon village of Walesam is first recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086. The derivation of the name itself tells us that it was a small group of dwellings, Anglo-Saxon: -ham meaning ‘home of’ or ‘homestead’ in Old English.

Toponymy reveals various interpretations of the name, the most likely is it relates to a person’s name ‘W(e)alh’ and his or their family home. Norfolk has a high concentration of Anglian or Anglo-Saxon name-endings such as the early -ingham and slightly later -ham and -ton. The appearance of this name-ending tells us that the family probably settled here sometime in the sixth century AD.

There is also a possibility that it could originate from the Old English ‘Walh’ meaning Briton or Welshman. This may also be the case with Walcott (Walh’s house or cottage). So it could possibly be related to the foundation of a settlement by an older group of the original British or Romano-British population in the area some of whom would have assimilated while others chose to move west with the influx of Anglians, Saxons and Friesians, settlers from what is now Northern Germany and the low-countries. Perhaps also consistent with the idea that there may be a Romano-British link, in 1844 Roman remains were found on the parish border with Felmingham; a site close to the line of a Roman Road which connected Burgh Castle near Great Yarmouth to the great fort at Brancaster on the northwest Norfolk coast.

The third, least likely, but most romantic idea is that it may possibily relate to the name ‘Waels’ or ‘Waelsing’ family who feature in the famed Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf, written about a sixth century warrior who slayed Grendel, serpent of the Fens. Waels was the father of Sigemund the Waelsing who slayed a hoard-keeping dragon.

It is conjectured that other settlements such as Walsham-le-willows, South Walsham and Walsingham may also come from the same Anglo-Saxon name root.

With the coming of Christianity to East Anglia, the village was provided with a church, and to that church a portion of land and a priest. When the Vikings later raided the shores of eastern England many a village fell to their hands, including Walsam. It is recorded that during the reign of King Canute, a Norseman named Skiotr gave the village of Walsam along with its church and estates to the Abbey of Saint Benet at Holme, then sited on an island in the Bure marshes near Horning. This Abbey was to become one of the richest Benedictine Monasteries in the land. Much of this wealth was obtained from Walsam, being its principal and most prosperous holding. The Abbot of Saint Benet’s as Lord of the Manor held the rights to all tithes, and as the weaving industry of the area flourished these tithes became lucrative. It was upon this great wealth that the Abbey Church of Saint Benet along with the Parish Church of North Walsham were enlarged on a grand scale in the fourteenth century. Through this the town can now boast the largest church in Norfolk that has always been solely a parish church.

(Note: Both King’s Lynn Minster and Great Yarmouth Minster are larger buildings but were originally conceived as priory churches. Great Yarmouth Minster holds claim to being the largest parish church in England.)

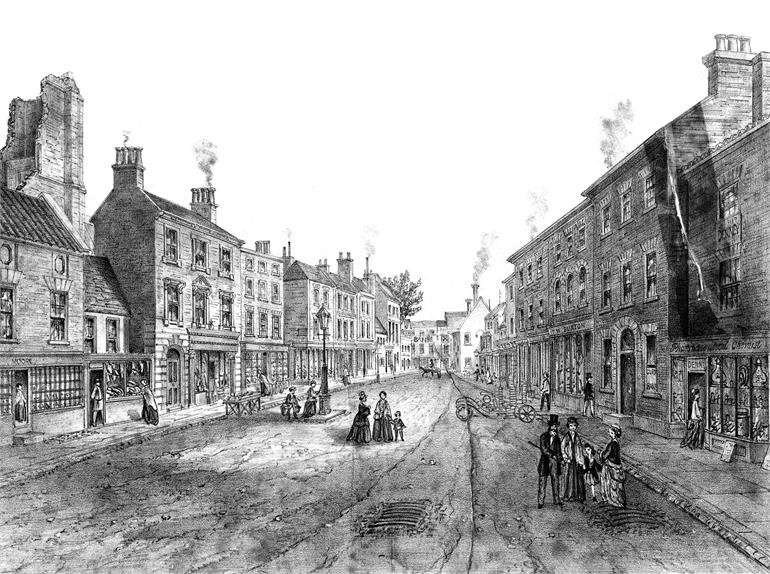

Records throughout the ages mention the town as Walsham Market and Walsham, the ‘North’ being added within the last few hundred years. The Domesday book tells us that a church existed in North Walsham and that it belonged to Saint Benet’s Abbey. The tower of this ancient church still exists today, being the oldest building in the town at well over a thousand years old. It was incorporated into the present church building and stands to the immediate north of the present tower ruin. Most of the town was built of wood at this time, being thatched with the reed that grew in the water meadows of the River Ant on the east side of the town. The town’s arable land was divided into three fields; Southfield, Millfield and Northfield, and were subdivided into strips allotted to the townsfolk. This was a system common throughout the country, with one field sown in wheat, another in beans, with barley for brewing, and the third left fallow for sheep to re-fertilize the land. Year by year this system was rotated so that all fields had equal usage. The outskirts of the town were well wooded and provided rough grazing for wild boar.

Weaving and ‘Walsham’

Flemish weavers came to England in the twelfth century and settled in Norfolk, the low lying landscape being reminiscent of their homelands. Their weaving capitals were sited at the twin-towns of Worstead and Walsham; weaving the country’s finest cloths of ‘Worsted’, still famed for its quality worldwide, and ‘Walsham’; which was a lighter cloth for summer use. By the beginning of the fourteenth century a market of these cloths was well established in Walsham. This new prosperity was proudly flaunted with the building of vast new churches for the two towns. More Flemish weavers moved to the district at the invitation of Edward III, and the town flourished at an incredible rate until 1348 ... the coming of the ‘Black Death’.

‘Black Death’ and Peasant Unrest

The Bubonic Plague or ‘Black Death’ ravaged England in 1348, and recurred in 1361 and 1369. With it came the death of thousands, resulting in a loss of labour needed to farm the land, and work on Walsham’s incomplete church; the original plans had to be altered, and simple intersected window tracery was substituted for the planned beautiful decorated tracery. With the economy of the country in turmoil an Act was passed in 1351 that no man should refuse to work for the same rate of pay as before the Black Death. Extra revenue was also generated by the imposition of a Poll Tax on the people. The arable fields were laid to pasture, and common land was enclosed for sheep farming. This was less labour intensive with more profit being made from wool production. This caused great unrest of the peasants, which led to the famous ‘Peasants’ Revolt’ of 1381 when John Litester, assisted by amongst others a man called Cubitt of North Walsham, led a rebellion of many thousands who seized the city of Norwich, killing the mayor in the process. Henry De Spenser, Bishop of Norwich, and a man with much experience of war abroad, was able to raise enough forces to drive the rebels from the city and they retreated to a camp at Bryant’s Heath near North Walsham. Despite the peasants’ elaborate makeshift barricades, they were ousted from their camp by the Bishop and his now numerous forces, and battle commenced. Many hundreds were slain and the defeated peasants fled towards the town desperately seeking their right of ‘sanctuary’ in the church, however, it was still incomplete and yet to be consecrated. The Bishop followed, Litester was captured, and the church witnessed a massacre of hundreds of peasants. De Spenser heard Litester’s confession, gave him absolution and then had him dragged to his public execution. Three stone crosses were soon erected marking the site of the battlefield, as a permanent reminder of the consequences of such uprisings.